Introduction

DSL (Domain-Specific Language) is becoming increasingly popular. More and more DSLs are developed for solving various domain-specific problems. A well-designed DSL should be easy to use, which requires a well-defined syntax and a good compiler that can report all potential errors in a meaningful way.

There are three kinds of compilation errors: syntactic errors, resolution errors, and semantic errors. A good compiler should have a forgiving grammar such that it reports less syntactic errors but more semantic errors, because semantic errors are generally more user-friendly. In this article we will focus on semantic errors.

Error reporting has been considered a hard part of compiler construction. How should we discover all the validation rules to avoid reporting something like “an unknown error”?

I’ve been doing some experiments with Alloy for this. Alloy is a language for modeling and analyzing software design. For a DSL, we can define an Alloy model for its semantic model and let Alloy simulate both “good” and “bad” examples, which can help us discover the validation rules of the DSL. We can also define assertions to check whether a presumably well-formed semantic model satisfies the validation rules. If Alloy discovers any counterexamples, we can analyze them to gain deeper understanding of the semantic model and even discover new validations rules. Alloy’s ability of performing a bounded exhaustive analysis under a given scope can greatly improve the coverage of the validation rules.

In this article, I will use a state machine DSL as an example.

State Machine DSL

State machines are widely used in software development. A state machine DSL defines some states, events, and transitions. A transition, that causes the state of the machine to be changed from one state to another state, can be triggered by an event, or a guard, or both. A guard is a condition that evaluates to true or false. A guard g1 can overlap another guard g2 when g1 implies g2. For example, the guard temperature > 90 overlaps temperature > 100.

The following is an example of the StateMachine DSL.

states initial, powerOn, operating, idle, powerOff, final

events turnOn, turnOff

transitions

initial -> powerOn turnOn

powerOn -> operating

operating -> idle [reachUpperLimit]

idle -> operating [reachLowerLimit]

operating -> powerOff turnoff

powerOff -> final

The DSL code describes the state machine of a simple toaster machine, that has 6 states: initial, powerOn, operating, idle, powerOn, and final, with initial as the start state. When the event turnOn occurs the machine powers on, and the user can set the upper and lower temperature limits. The machine then enters the operating state. When the temperature reaches the upper limit, the heater turns off, and the machine enters the idle state. When the temperature reaches the lower limit, the heater turns on, and machine enters the operating state. When the turnOff event occurs, the machine enters the powerOff state, and eventually enters the final state.

The Alloy model of the DSL

An Alloy model consists of some signatures, facts, functions, predicates, and assertions.

Signatures

A signature is like a class in object-oriented program. The keyword sig introduces a signature.

The signature Name represents a name of something.

sig Name {}

The signature State represents a state of a state machine.

sig State {

name: Name

}

The signature Event represents an event that can cause a state transition.

sig Event {

name: Name

}

Both State and Event have a field name, which introduces a relation from State to Name, and from Event to Name, respectively.

The signature Guard represents a guard for a transition to occur. A guard can possibly overlap another guard.

sig Guard {

overlap: lone Guard

}

Now we can define the signature for transitions.

sig Transition {

pre, post: State,

event: lone Event,

guard: lone Guard,

}

The pre and post fields represent the pre- and post-state of a transition. A transition can be triggered by an event, a guard, or both. A transition with neither an event nor a guard will be triggered automatically when the state of the machine enters the pre-state of the transition.

With these signatures defined, we can define the signature, StateMachine, that consists of a set of states, a set of events, and a set of transitions. The field startState, which denotes the start state of the state machine, is one of the states of the state machine.

one sig StateMachine {

states: set State,

startState: states,

events: set Event,

transitions: set Transition,

}

The keyword one before the keyword sig says that there will be only one StateMachine atom in our model, to reflect that fact that one StateMachine DSL file defines only one state machine.

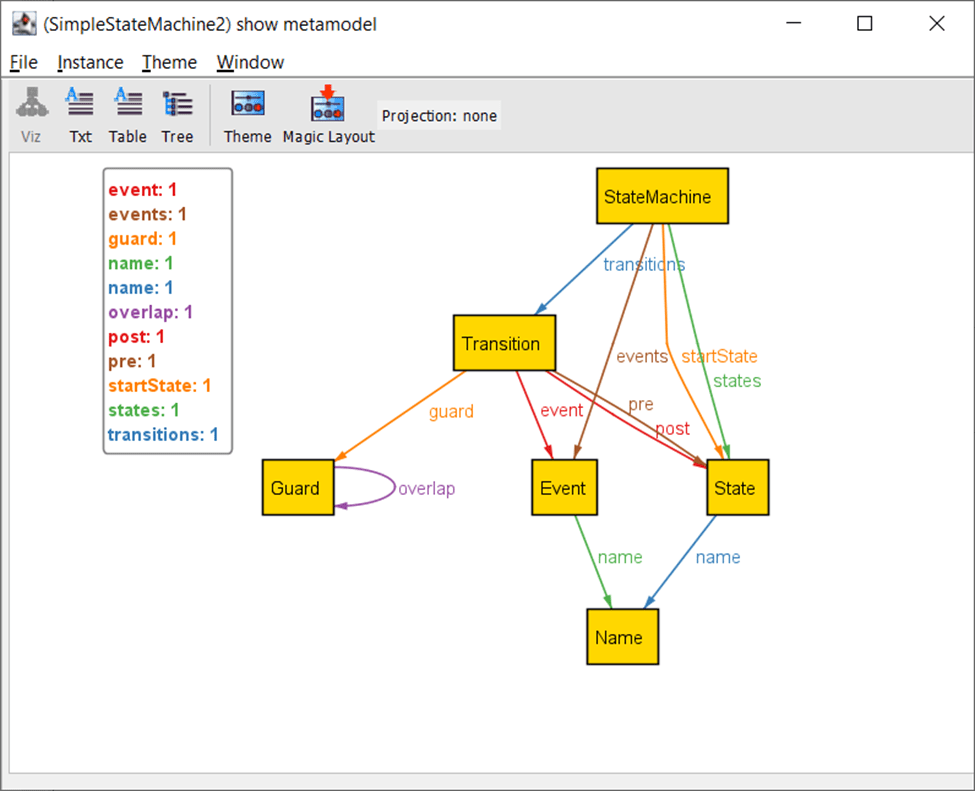

Now we can ask Alloy to generate the metamodel as shown in Figure 1, which looks very similar to a UML class diagram.

Figure 1. The metamodel of the StateMachine DSL

Showing examples

After we have defined the signatures, we can ask the Alloy tool to generate some examples by running the following command, which tells Alloy to find an example that has some states, transitions, and guards, within the scope that has at most 4 atoms of each top-level signature:

run show_example {

some State

some Transition

some Guard

} for 4

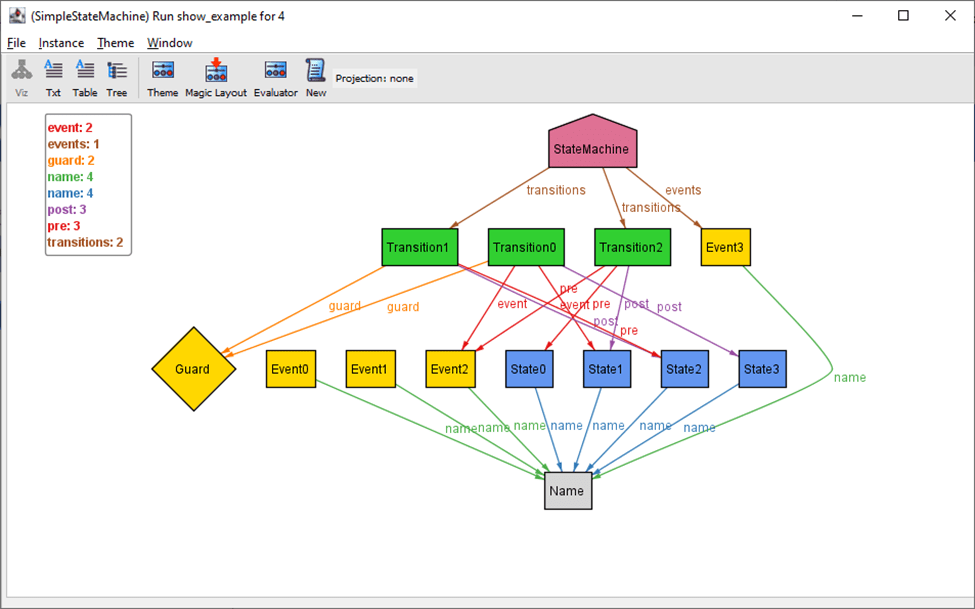

Figure 2. An example

Figure 2 shows an example, from which we can immediately observe two obvious issues: 1) all the events and states have the same name, and 2) some transitions, events, and states don’t belong to the state machine.

A reasonably good parser should be able to detect these kinds of issues and enforce that the generated semantic models are free from these issues. Since we focus on the semantic errors of the DSL in this article, we can define some facts to assume that, in a state machine semantic model:

- Each state has a unique name,

- Each event has a unique name,

- All states, events, transitions, and guards, defined in a state machine DSL file, belong to the state machine.

Facts

Facts are constraints that are assumed to always hold.

The fact “unique_names” ensures that all different states and all different events have different names.

fact “unique_names” {

all disj s1, s2: State | s1.name != s2.name

all disj e1, e2: Event | e1.name != e2.name

}

The fact “ownership” states that all states, transitions, and events belong to the state machine; and all guards belong to the transitions, meaning there shouldn’t be any standalone states, transitions, events, or guards.

fact “ownership” {

State in StateMachine.states

Transition in StateMachine.transitions

Event in StateMachine.events

Guard in Transition.guard

}

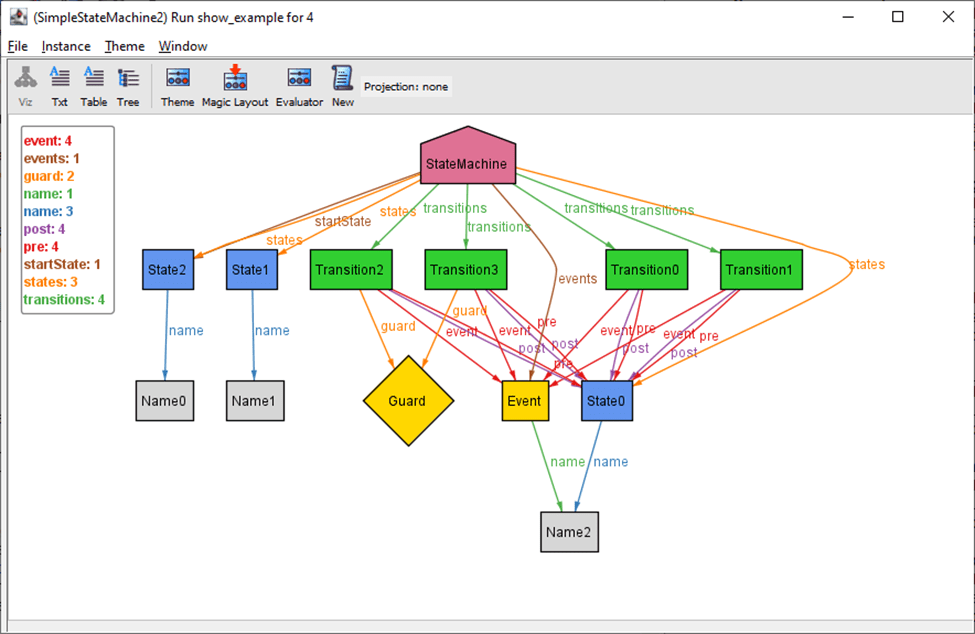

With the facts defined, we can run the command again to generate some new examples. Figure 3 shows a more reasonable but still invalid state machine, because both Transition0 and Transition1 cause State0 to be transitioned to same state when Event occurs, and State1 and State2 have no incoming and outgoing states, etc.

Figure 3. A more reasonable but still invalid example

We could keep clicking on the New button to show other examples until Alloy exhausts all instances under the given scope. We can examine the examples together with domain experts to discover the validation rules, and define the rules as Alloy predicates.

Predicates

A predicate is a constraint, which evaluates to true or false when called. We define one or more predicates for each validation rule.

Preparation

Before defining the predicates for the validation rules, let’s do some preparation.

First, we define an auxiliary function NextStates, which returns a relation from all states to their next states, for Alloy to show the connections from each state to its next states.

fun NextStates: State -> State {

{ from, to: State | some t: Transition | from = t.pre and to = t.post }

}

Next, we define a predicate to constrain that all state machines are well-formed. Whenever we define a validation rule, we will add the predicate for that rule to the WellFormedStateMachine predicate.

pred WellFormedStateMachine {

all sm: StateMachine {

— validation rules

}

}

And finally, we define a command for Alloy to find an example of a presumably well-formed state machine that has some state, some transitions, some guards with overlapping. We can run the command whenever we want to examine some examples.

run show_well_formed_example {

WellFormedStateMachine

some State

some Transition

some Guard

some Guard.overlap

} for 4

Now, let’s define the validation rules. Note that the rules may not be defined in one shot. Instead, they are normally discovered step by step.

Rule 1, each state machine shall have a single start state that shall have exactly one outgoing transition and no incoming transition.

For this rule, we define the predicate WellFormedStartState that states that there is no transition whose post state is the start state, and there is exactly one transition whose pre-state is the start state.

pred WellFormedStartState[sm: StateMachine] {

let start = sm.startState {

no s: sm.transitions | s.post = start

one t: sm.transitions | t.pre = start

}

}

Rule 2, all states shall be reachable

The predicate AllStatesReachable verifies that for each state s except for the start state, there shall be some transition that comes to s but not from itself.

pred AllStatesReachable[sm: StateMachine] {

all s: sm.states – sm.startState | some t: Transition |

t.post = s and t.pre != s

}

Rule 3, all transitions shall be deterministic

This rule means that, for each state, the transitions from the state shall meet the following requirements:

- Either all transitions are triggered by events or none of them is triggered by an event,

- If some transitions are triggered by the same event, they should have different non-overlapping guards,

- If the transitions are not triggered by events, they should have different non-overlapping guards.

Before defining the predicate, let’s define some functions to make the Alloy code more concise and easier to read. A function is introduced by the keyword fun.

The function IncomingTransitions returns all incoming transitions of a state.

fun IncomingTransitions[sm: StateMachine, s: State]: set Transition {

{ t: Transition | t.post = s }

}

Likewise, the function OutgoingTransitions returns all outgoing transitions of a state.

fun OutgoingTransitions[sm: StateMachine, s: State]: set Transition {

{ t: Transition | t.pre = s }

}

We define a predicate to detect whether two Guards have any overlap.

pred Overlap[g1, g2: Guard] {

some (g1.*overlap & g2.*overlap)

}

Now we can define the predicate to detect whether all transitions are deterministic.

pred DeterministicTransitions[sm: StateMachine] {

all s: sm.states | let outgoing = OutgoingTransitions[sm, s] {

#outgoing > 1 => {

all disj t1, t2: outgoing {

t1.event != t2.event => #(t1.event + t2.event) = 2

else #(t1.guard + t2.guard) = 2 and !Overlap[t1.guard, t2.guard]

}

}

}

}

Rule 4, there shall be at most one black-hole state.

A black-hole state is a state that has no outgoing transitions. Each state machine shall have at most one black-hole state, which is the final state.

We define a function that returns all black-hole states of a state machine.

fun BlackHoleStates[sm: StateMachine]: set State {

{ s: State | no t: Transition | t.pre = s and t.post != s }

}

And define a predicate to check that the number of black-hole states is at most 1.

pred AtMostOneBlackHoleState[sm: StateMachine] {

#sm.BlackHoleStates <= 1

}

Rule 5, all declared events should be used by the state machine.

This rule checks whether all events declared by a state machine are actually used. This is a warning instead of an error, and therefore, it won’t be added to the WellFormedStateMachine predicate.

pred AllEventsAreUsed[sm: StateMachine] {

sm.events in sm.transitions.event

}

Well-formed predicate

With all the predicates defined for the validation rules, the WellFormedStateMachine predicate becomes:

pred WellFormedStateMachine {

all sm: StateMachine {

sm.WellFormedStartState

sm.AllStatesReachable

sm.DeterministicTransitions

sm.AtMostOneBlackHoleState

}

}

Well-formed examples

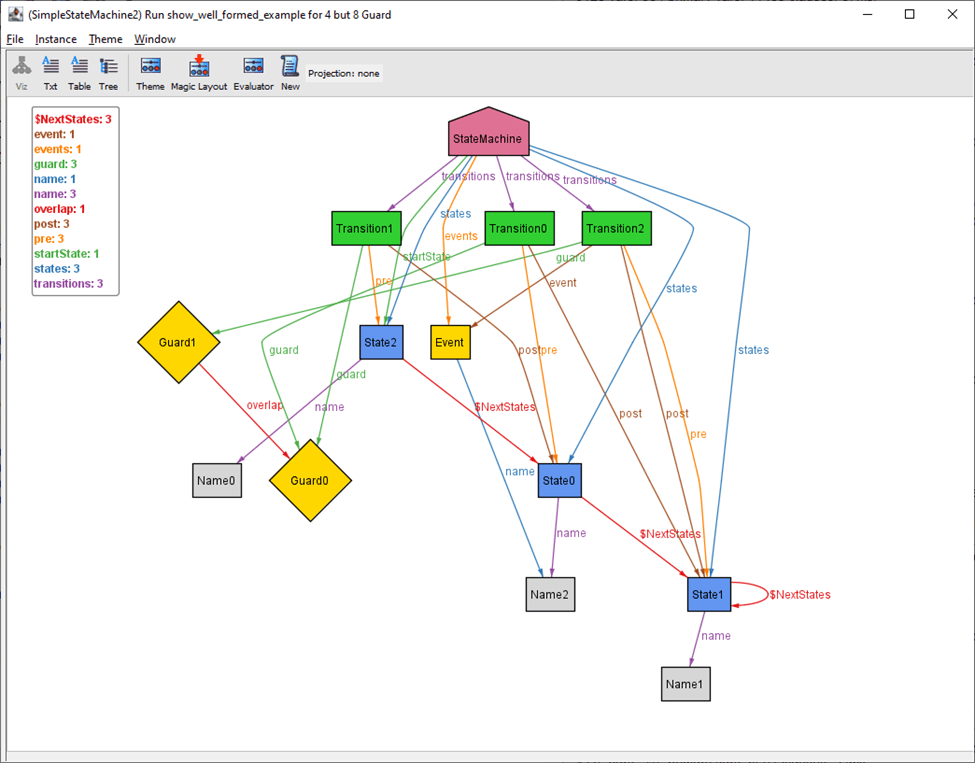

By running the show_well_formed_example command, Alloy will show us examples of well-formed state machines. Figure 4 shows an example, in which, State2 is the start state, which transitions to State0 when Guard0 is satisfied; when Guard0 is satisfied, the state transitions to State1; and when Event occurs and Guard1 is satisfied, the state transitions to State1 itself.

Figure 4. A well-formed example

We can continue pressing the New button to show new examples and see whether there are any surprises. If there is any, it is a good opportunity for us to gain deeper understanding about the semantic model and to discover new validation rules.

Besides browsing the examples manually, we can also ask Alloy to find counterexamples, if any, automatically, by defining assertions.

Assertions

An assertion is something that we believe to be true. If Alloy finds any counterexamples for an assertion, it means something is wrong with our understanding. Assertions are like unit tests in software development, which give us confidence to modify the Alloy code.

Assertion 1, in a well-formed state machine, the start state has no incoming transition and exactly one outgoing transition.

check start_state {

WellFormedStateMachine => {

all sm: StateMachine {

one t: Transition | t.pre = sm.startState

no t: Transition | t.post = sm.startState

}

}

}

Assertion 2, all transitions are deterministic in a well-formed state machine.

The assertion no_nondeterministic_transitions checks that for all distinct transitions t1 and t2 from the same state in a well-formed state machine, either they have different events or they have different non-overlapping guards.

check no_nondeterministic_transitions {

WellFormedStateMachine => {

all sm:StateMachine {

all disj t1, t2: sm.transitions | t1.pre = t2.pre => {

t1.event != t2.event => #(t1.event + t2.event) = 2

else {

let g1 = t1.guard, g2 = t2.guard {

#(g1 + g2) = 2

no (g1.*overlap & g2.*overlap)

}

}

}

}

}

} for 8 but 10 Guard

Assertion 3, there is only one miracle state in a well-formed state machine.

A miracle state is the one that has only outgoing transitions. In a well-formed state machine, only the start state should be a miracle state.

check only_one_miracle_state {

WellFormedStateMachine => {

all sm: StateMachine {

one s: sm.states | no IncomingTransitions[sm, s]

}

}

} for 8

Assertion 4, there is at most one black-hole state.

In a well-formed state machine, there is only one state that has no outgoing transitions.

check at_most_one_back_hole_state {

WellFormedStateMachine => {

all sm: StateMachine {

lone s: sm.states | no OutgoingTransitions[sm, s]

}

}

} for 8

Running the assertions reveals no counterexamples, which means the validation rules are consistent with our understanding about the semantic model of the DSL.

Discussion

My experiments show that Alloy is a great tool for us to understand the semantic model and to define the validation rules of a DSL. Here are my key takeaways from the experiments.

When defining the signatures of the semantic model, use “more relaxed relations”. For example, when the semantic model requires a relation to be one-to-one, define the relation as one-to-zero-or-one, to allow the parser to have more relaxed grammar rules, such that we can report a more user-friendly semantic error instead of a syntactic error.

Define the constraints that the parser and the identifier resolver can enforce as facts. Doing so will allow us to focus on the validation rules of the semantic model.

Define predicates for all validation rules of the semantic model. Don’t define validation rules as facts. Otherwise, we won’t be able to ask Alloy to show the examples that violate one or more validation rules. Being able to examine the examples is very helpful for us to understand the semantic model.

Define a predicate for checking whether a semantic model is well-formed, by calling the predicates defined for all validation rules. This predicate will be handy when we define a command to show well-formed examples, or when we want to assert certain properties of a well-formed semantic mode should hold.

Define auxiliary functions, when necessary, to improve the visualization of the semantic model examples.

Define commands for showing well-formed, or partially well-formed examples. Examine the examples with domain experts. These examples can provide us ideas when we write unit tests for the compiler of the DSL.

Define assertions for each validation rule. Keep adding new assertions when new insights are discovered. For well-known validation rules, we may want to define the assertions even before we define the predicate for them.

References

Daniel Johnson. Software Abstractions, revised edition.

Martin Fowler. Domain-Specific Languages

Scott W. Ambler. The Elements of UML 2.0 Style

The Alloy code for the state machine DSL

module state_machine

sig Name {}

sig State {

name: Name

}

sig Event {

name: Name

}

sig Guard {

overlap: lone Guard

}

sig Transition {

pre, post: State,

event: lone Event,

guard: lone Guard,

}

one sig StateMachine {

states: set State,

startState: states,

events: set Event,

transitions: set Transition,

}

fact {

State in StateMachine.states

Transition in StateMachine.transitions

Event in StateMachine.events

Guard in Transition.guard

}

fact “unique_names” {

all disj s1, s2: State | s1.name != s2.name

all disj e1, e2: Event | e1.name != e2.name

}

fun IncomingTransitions[sm: StateMachine, s: State]: set Transition {

{ t: Transition | t.post = s }

}

fun OutgoingTransitions[sm: StateMachine, s: State]: set Transition {

{ t: Transition | t.pre = s }

}

fun BlackHoleStates[sm: StateMachine]: set State {

{ s: State | no t: Transition | t.pre = s and t.post != s }

}

pred WellFormedStartState[sm: StateMachine] {

let start = sm.startState {

— The start state has no incoming transition

no s: sm.transitions | s.post = start

— The start state has exactly one outgoing transition

one t: sm.transitions | t.pre = start

}

}

pred AllStatesReachable[sm: StateMachine] {

all s: sm.states – sm.startState | some t: Transition | t.post = s and t.pre != s

}

pred AtMostOneBlackHoleState[sm: StateMachine] {

#sm.BlackHoleStates <= 1

}

pred Overlap[g1, g2: Guard] {

some (g1.*overlap & g2.*overlap)

}

pred DeterministicTransitions[sm: StateMachine] {

all s: sm.states | let outgoing = OutgoingTransitions[sm, s] {

#outgoing > 1 => {

all disj t1, t2: outgoing {

t1.event != t2.event => #(t1.event + t2.event) = 2

else {

let g1 = t1.guard, g2 = t2.guard {

#(g1 + g2) = 2

no (g1.*overlap & g2.*overlap)

}

}

}

}

}

}

pred AllEventsAreUsed[sm: StateMachine] {

sm.events in sm.transitions.event

}

pred WellFormedStateMachine {

all sm: StateMachine {

sm.WellFormedStartState

sm.AllStatesReachable

sm.DeterministicTransitions

sm.AtMostOneBlackHoleState

}

}

— Auxiliary function

fun NextStates: State -> State {

{ from, to: State | some t: Transition | from = t.pre and to = t.post }

}

run show_example {

some State

some Transition

some Guard

} for 4

run show_well_formed_example {

WellFormedStateMachine

some State

some Transition

some Guard

some Guard.overlap

} for 4

run show_multiple_outgoing_transitions {

WellFormedStateMachine

some sm: StateMachine, s: sm.states | #OutgoingTransitions[sm, s] > 1

} for 4

check start_state {

WellFormedStateMachine => {

all sm: StateMachine {

one t: Transition | t.pre = sm.startState

no t: Transition | t.post = sm.startState

}

}

}

check no_nondeterministic_transitions {

WellFormedStateMachine => {

all sm:StateMachine {

all disj t1, t2: sm.transitions | t1.pre = t2.pre => {

t1.event != t2.event => #(t1.event + t2.event) = 2

else {

let g1 = t1.guard, g2 = t2.guard {

#(g1 + g2) = 2

no (g1.*overlap & g2.*overlap)

}

}

}

}

}

} for 8 but 10 Guard

check only_one_miracle_state {

WellFormedStateMachine => {

all sm: StateMachine {

one s: sm.states | no IncomingTransitions[sm, s]

}

}

} for 8

check at_most_one_back_hole_state {

WellFormedStateMachine => {

all sm: StateMachine {

lone s: sm.states | no OutgoingTransitions[sm, s]

}

}

} for 8

check all_events_are_used {

all sm: StateMachine {

AllEventsAreUsed[sm] => {

all e: sm.events | some t: sm.transitions | e = t.event

}

}

} for 8

Leave a comment